Fat Cells

(I wrote this in the early 2000s and delivered it as a speech at three different high schools. It was a long time ago, and who cares, but when I re-read it the other day, I felt proud of the sentences and the ideas. In the age of Ozempic, it may be even more relevant.)

A few years ago I weighed in the neighbourhood of 400 pounds. Big neighbourhood. By this past spring, I was 250. At 6’5” I can get away with 250. I can browse the XL aisles in department stores instead of the 4XL rack at the big and tall shops. In the years it took to lose the weight, I rode the dieter’s roller coaster. I’d drop 40, gain 10, then level off. Trim another 50, hold steady for a while, and pack on 15. Drop 20, add 10, and so on. This spring, after a year on a sensible diet and a vigorous exercise program, I reached my goal.

I have been asked many times by colleagues and former students what it feels like to lose so much weight. “Great!” I always say. “Just great . . . like the Incredible Journey. Like a Christmas present hidden at the bottom of a big, big box. Like walking very slowly out of jail.”

To be honest, I don't feel much different. I didn't wake up fat one day. I didn’t get zapped by the fat fairy. I gained weight a pound at a time and learned to walk with it day-by-day, the way we learn to carry any accumulating burden. And I lost it a pound at a time, too, so the relief came slowly. It's not physical relief anyway. I don’t feel like a dancer. Mostly I just don't feel embarrassed all the time.

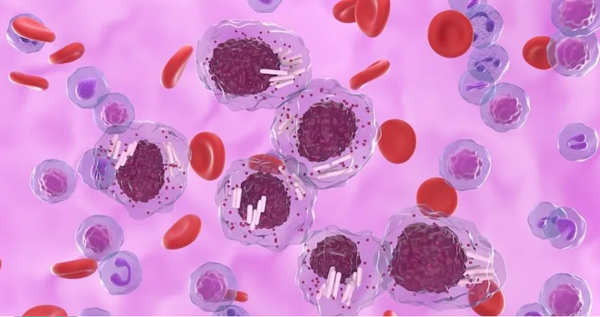

Fat cells don’t go away. Once you’ve been fat, you remain predisposed to obesity. Pre-adiposed, I guess. Inside anyone who has lost a lot of weight lie billions of fat cells hungering after their former glory. Sometimes I think those starving fat cells comprise a fat self, a shadow personality whose intimacy with otherness forms ominous shapes in the mind. What if I were still my fattest? I sometimes think during conversations with friendly new acquaintances. Would we be having this conversation?

*

The stereotype says that fat people are jolly—or it used to, at least. Despite the thickening North American waistline, popular culture abhors fat. We’ve learned (publicly, at least) not to dishonour people for their gender, for their skin colour, for their sexuality or their ethnicity. But a fat person often feels like a punch line waiting to happen. We learn to mock ourselves to remove from others the opportunity to snicker. If you’ve ever heard and felt the gurgling contempt of people snck-snck-snck-ing in your direction, then you may understand the fat person’s daily predicament.

Some people believe that corrective cruelty is a public service. “Whhhhaaaaat?” they’ll say if you question their pointed insults. “I’m kidding! But come on—seriously!—you need to lose some weight . . . for your own good.”

Once, in the staff room of a school where I was teaching, I knelt on the seat of a chair and leaned out the window to call after a student. One of my colleagues passed behind me. “Thank God for clothes,” he muttered, much to the amusement of several of his coaching pals.

I’m a jolly guy. I like a good joke. I laughed along with the others.

*

But being fat, like being mean or insensitive, is complicated.

One year, when I was at my fattest, I had a part in a play. I wore a black tuxedo and a red silk scarf. I thought I looked good. A tuxedo makes for stylish armour, and I believed people saw the suit, not me. We played first to an audience of middle school kids. During the intermission, a small group of boys slouched by while I was smoking a cigarette behind the theatre (I was afraid to quit in case—well, you know . . .). The kids had decided to ditch the show for the mall. One of them caught sight of me and said, “Hey, it's the fat guy from the play. Hey, fat guy!” This was followed by a burst of laughter from the others and a chorus of “Hey, fat guy . . . fat guy . . .”

That kind of thing rarely makes you want to diet. It makes you want to grab a bottle or a Big Mac and disappear.

But you learn resilience, too. You acquire a willingness to confront the subtext that controls so many social situations.

I needed to fly to Edmonton one winter for a project I was involved with. A friend diplomatically suggested I might not fit in a regular airplane seat. I didn’t want to pay $800 to fly first class, so I phoned the airline and talked to a pleasant young woman about the problem. We fumbled back and forth across the telephone line and tried to determine whether or not I would fit into one of their seats.

She said, “Well, um . . . how big are we talking here?”

And I said, “Well, you know . . . big.”

We couldn’t figure it out over the phone, and I refused to drive to their hangar to demo a chair. To be safe, I spent $550 on side-by-side coach seats.

When I boarded the plane, I discovered I would have been okay with just one ticket—sort of—as long as I leaned into the aisle. It’s an awesome feeling to fit into the world and its furniture.

I was enjoying my chair and enjoying not having anyone beside me when I saw another fat man three rows back, also with an empty seat beside him. I looked at him, and he looked at me—and then he said what everyone on the plane was thinking: “Hey! You wanna sit together! BWA-HAHAHAHAAA!”

*

I grew fat because of my attempts to satisfy my constant cravings. I can’t say why I didn’t care about the transformation of my body. My mother spent a lifetime worrying about her weight, though she was never fat, merely heavier than she wanted to be. What she wanted to be, I suppose, was as thin as the most attractive and stylish of her friends. Her fear found a home in me—and warped, as such things do. I was a stocky kid—not fat, I realize when I look through family pictures. Not skinny, either. Stocky. But from the moment a wiry little scrapper named Richard called me “Jelly Belly” in grade four, I felt fat. The tag stuck, and for a time that was the name I answered to at school. There’s nothing more dangerous than a negative conviction. “The first cut is the deepest,” the saying goes. I’d modify the phrase this way: the first loathing is the strongest.

I do not mean to suggest I grew fat because I was labeled with an unfortunate nickname. It was simply architecture for the complex self-loathing many of us acquire when we’re young. In my own case, the transformation was insidious. Appetite mutated into craving, and soon I carried a far deeper hunger. I ate because it made me feel good. By the age of 13, I was six foot two, 240 pounds.

Sports and an interest in girls helped me shed pounds during my adolescence. In my college basketball picture, I weighed 192 pounds. In my wedding photos, taken three years later, I weighed 216. The twenty-pound gain set the alarms ringing, but I couldn’t escape the building. By my 35th birthday I weighed 390 pounds.

“How does that happen?” I’ve been asked.

We all have magic eyes, for one thing. We walk slowly into prisons of our own making. People who gain a great deal of weight—or let their drinking go from glass to bottle, or grow addictive in any realm—know this mantra: “It’s not so bad.” We can’t see the changes day-to-day, so we accommodate the increments.

Even during the years of rapid weight gain, I looked in the mirror as much as anyone. Maybe more than most. I’d nod, find the most flattering angle, eye up my strongest features, and adjust. Relative to the troubles endured by the diseased and the destitute, I had nothing to complain about. “It’s not that bad,” I told myself.

Then one day we confront our disbelief like parents who return from a weekend away to discover their home decimated by a teen party gone wrong: “What the hell happened here?” Unfortunately, it’s difficult to force a remedy on a dire situation.

My father was so alarmed by my rapid weight gain that he bought me an expensive mountain bike. I cycled carefully around the parking lot at the bike shop while he paid the clerk. “This is great,” I said to my wife when I unloaded the bike at home, but I hated that bicycle—hated the bright blue steel tubes and knobby tires, hated the narrow saddle and the stupid little bell on the handlebars. When you’re fat and not yet ready to deal with it, exercise is humiliating. You understand the link between activity and weight loss, but the effort required to change is disheartening. The strain of it. The foolishness of athletic costumes on a big, round body. The embarrassing jiggle and sway of exertion. It feels easier to live with the problem than to endure the solution.

Nonetheless, I dutifully went riding with my oldest son, who was 8 or 9 at the time. At the crest of a very short, very steep hill, I rose on the pedals and thrust my right leg mightily downward. There was almost no resistance in the pedal. Suddenly I toppled over. I looked at the bike to see the rear portion of the frame twisted like taffy. The bike was only a month old. I probably could have claimed a new one against the warranty. Instead, I dumped it in the bushes nearby and walked the kilometer home with my son riding silently beside me.

*

When you’re truly fat, you watch others closely and learn that a lot of people are fat in their own way. Fat is just an unhealthy burden of some kind—something you want to get rid of. Physical fat is one kind of weight, but there are much darker breeds of obesity. You can be fat with envy. Obese with prejudice. Hate-fat. Everyone has some ugly to lose.

Self-knowledge, of course, is elusive. We don’t see ourselves as we are; we see ourselves as we believe others see us. And when we don’t like what they see, we tear ourselves apart. For example, both my sons had bad skin. One of them suffered through high-dosage Accutane treatments to poison the acne from his system. The other tried laser treatments. I wish they could have endured the troubles, thrown their shoulders back, and waited for the phase to pass. But my own battles told me that was naïve. When he was 21, the elder boy told his brother and me, “I got tired of people looking at me like they didn’t know where to look.”

“I know,” I said.

“Now that my skin is normal,” the 17-year-old added, “I’ll be talking to someone who has known both my faces, and I’ll see something different in their eyes. Like I’m finally okay.” After a moment, he said, “I just hope it doesn’t come back.”

“I know,” I said.

*

I have learned that connection to others allows us to ease our burdens.

One afternoon when I was still very heavy, I was asked to cover a grade 8 social studies class for an ailing colleague. Toward the end of the period, I was seated behind the teacher’s desk when the noise level began to rise in the classroom. The students were meant to be working, but their attention had begun to fray. I pointed at some troublemakers and issued a standard teacher warning: “Would you like to stay an extra fifteen minutes at the end of the day?”

At that moment my chair collapsed. The rivets must have been loose to begin with, and I was a burden too great to bear.

For 13-year-olds, sight gags don’t get any better than a fat man collapsing through the steel tubes and molded plastic of an institutional chair. I think it’s safe to say it was the funniest thing many of them had ever seen. They laughed. Hard. One of them fell off his chair. I let the class go early.

As she was leaving, a horsy girl with big shoulders and a voice like sliding gravel stopped at my desk. “You’re my favorite teacher!” she blurted, then ran to catch up with the others.

For just a few moments, everything was okay.

*

At my largest, golf was the only exercise I could enjoy. After I’d dropped the first 50 pounds, I was in a group with an old friend. I confessed that the weight loss was making it easier to swing the club. My friend looked at me and raised an eyebrow, puzzled.

“Stephen,” I said, “I’ve lost 50 pounds." He looked at me as if to say, “I didn’t know you needed to lose weight.”

That sort of kindness came from my students, too. I never heard one of them call me fat. Many did, of course, but never in my hearing. When I started to lose weight, they remained silent, which puzzled me. My eldest son was in one of my classes, and after I'd dropped the first fifty or sixty pounds, I said to him, “Hey, I’ve lost weight, you know.'' Because he hadn’t said anything either.

He said, ''I know."

And I said, “Well, nobody ever says anything. Why doesn’t anyone say anything?"

He shrugged and said, “You know.”

“What?” I said.

And he said, “I don't think they want you to think that they thought . . . you know."

“What?” I said. “That I was fat?''

“Yeah,” he said.

And I thought, Wow.

A few days later, I said to one of my classes, “I’ve lost weight, you know.''

And they said, “Yeah, we know.''

I said, “You mean you knew and you didn’t say anything?”

“Yeah,” they said.

And I said, “Was it because you thought I'd think that you thought . . . ''

And they said, “Yeah.”

And I thought, Wow.