The Good Cancer

In mid-August 2022, of Maureen and I sat with the oncologist in a corner examination room of the BC Cancer Centre in Victoria. Dr. Freeman was in her thirties, soft-spoken and attentive, an acknowledged expert in her field. She had the slightly abstracted bearing of the highly intelligent, as if she were thinking from four different angles in any given moment. “You need treatment now,” she said.

I looked at Maureen. Something moved across her eyes. We had known this was coming, but now caught us both off guard.

Sometimes, of course, now was relative. I was initially diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in July of 2011 and advised to start treatment within a couple of months. I did not begin chemo until the following February. That 2012 toxic romp had pushed the cancer down for most of a decade, but left me with a burned-out immune system.

I explained to Dr Freeman that we planned to fly to Dawson City in a week to visit our youngest son.

“Why not begin treatment,” she said, “and then visit your son in a few months, when your blood has begun to recover?” Now, it turned out, meant now-now.

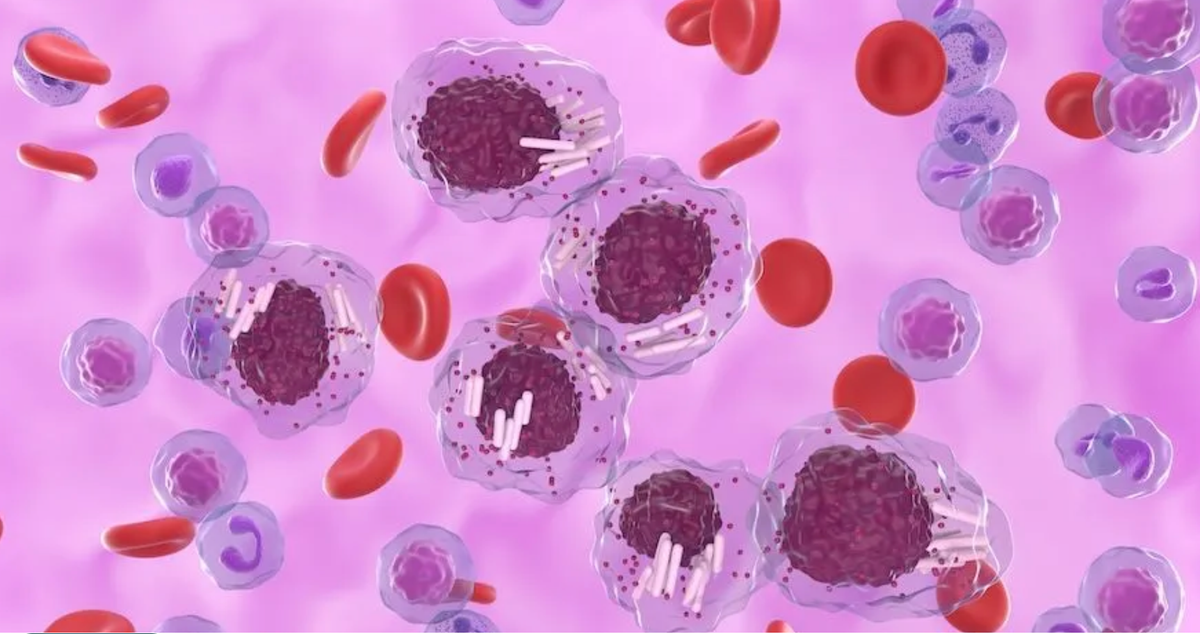

Flaring nodes had made me aware in late 2020 that the cancer was coming back, but the symptoms came and went. Leukemia can be sneaky like that. The average adult carries a white blood count of 4,000-10,000. In 2011, my WBC had risen to 135,000. Probably 95% of that number came from mutant lymphocytes--immature white cells that crowded my marrow, spleen, lymph nodes, and bloodstream. The descriptor of the cells as “immature” always made me grimace. Leave it to me to develop a cancer of childish cells.

The cancer was now manifest in a different way. CLL was causing trouble throughout my body. In the last 18 months, I had suffered a number of out-of-the-blue infections. I was anemic and fighting fatigue.

Dr Freeman suggested one of two targeted medications. In the years since my chemotherapy, “targeted” medications had come to dominate the CLL landscape. (Think of chemo as a nuclear bomb and targeted therapies as guerrilla operatives.) The new medicines were often more specific and less toxic.

I wanted the doctor to say that a targeted therapy would give me another long run of good health, but she drew the appointment to a close without making any promises. Oncologists don’t like to be specific in their optimism, even with a “good” cancer.

*

We rejected the doctor’s idea of postponing our trip. We seemed always to play my health with an abundance of caution. Nothing ever came of our anxiety, so this time we took the risk. A few days after we returned home from the Yukon, I landed in the hospital with covid.

For the first while, my only symptom was a mild cough. I felt confident I would recover without further medical intervention.

While I was making assumptions about the strength of my immune system, the virus burrowed deep into my lungs. A few days later, I was admitted to the hospital and isolated. I was barking up blood from double-pneumonia. The coughing spasms made a hammer of my rib cage. My spleen ruptured.

One of the nurses used a red felt pen to outline the massive bruise on my left side. “This way we can track the bleeding,” she said. If that wasn’t enough, an MRI revealed a blood clot in my lungs.

After a week in the hospital, I crashed. My blood-oxygen levels tanked and I was force-fed air from a chrome tap on the wall. Over a 48-hour period, the nurses fitted me with a series of different masks. Each alternative permitted higher air-flow, but eventually I maxed out. During my first x-ray after admission to the hospital, the technician had told me, “You have huge lungs.” Ten days later, even a shallow inhalation was like breathing soot. Anything more than a thin sip of air launched me into a raucous coughing jag.

In the elevator on the way to the acute care ward, the nurse said, “We can’t give you any more oxygen.” She meant I was at 100% of both the mechanical airflow and oxygen concentration a body can manage. I didn’t need a medical degree to understand that intubation was now on the list of options. I remember searching on my phone to find out how many covid patients survived intubation. It was somewhere between 40 and 60%.

Maureen told the supervising doctor that one of our sons lived far away and asked if she should arrange to bring him home.

“Yes,” he said without hesitating.

I remained in hospital for three more weeks. Even at the end of my stay, I could walk only about 15 metres unaided. The respirologist sent me home with two oxygen machines—one for around the house, plus a bread-box unit for adventures in mobility. At first, I could climb no more than four stairs and could walk only short distances, even with the oxygen machine slung over my shoulder like a teenager’s backpack.

Maureen pushed me to increase my strength and stamina. This meant daily bicycle rides over flat terrain—oxygen machine strapped to the rear rack of the bike—and monitoring my O2 levels with an oximeter clamped to my finger. I worked up to longer walks and more intense rides and eventually abandoned the supplemental oxygen. When I presented myself for cancer treatment at Royal Jubilee Hospital in Victoria in mid-November, the doctors were stunned by my robust appearance. Inside, of course, I carried a sobering appreciation for the razor-thin lines between sickness and health.

I had been sicker with covid than I’d ever been with cancer, but leukemia was the root problem.

In the grip of covid, I struggled to process oxygen and became severely anemic. Most of my time was spent staring at the ceiling lights and drifting toward depression. I couldn’t concentrate to read or even to watch a movie. High-dose steroids contributed to the insomnia and agitation.

Or maybe I was simply prepared. Cancer patients and survivors tangle daily with fear in one form or another. Physical disease drags the mind toward resignation. Even a good cancer makes immediate the inexorable reality that we all must one day let go.

There are a number of so-called “good” cancers. The five-year survivability for prostate, thyroid, testicular, and skin (melanoma) cancers is 99, 98, 97, and 94%, respectively. Even breast cancer now enjoys a 91% five-year survival rate. The nature of my disease profile at diagnosis in 2011 set my five-year chances at 50%, but my brand of leukemia stands with other “good” cancers. A CLL diagnosis often comes later in life and causes relatively little difficulty. It’s not uncommon for aging patients to be told they are more likely to die with CLL than from it.

I was diagnosed at 48, which put me 20 years or more ahead of the curve. I know of others diagnosed in their 30s.

“You may have had this for decades!” a senior oncologist at St. Paul’s in Vancouver told me at my second-opinion appointment. He held a thin file folder containing my test results. “But after this,” he said, slapping the folder with his free hand to indicate the proposed course of chemotherapy, “you could be fine for years.”

Good cancers are long on time and short on pain. (Count in this number any cancer caught early and treated quickly.) It’s possible I could survive 20 years from diagnosis. And if the St. Paul’s oncologist was right and the leukemia had already been developing for 10 years, then my run with cancer could stretch to three decades or more. Sometimes, when I feel overwhelmed, I tell myself I’m a badass survivor.

But the disease is chronic—inescapable. Many cancers can be cured through a combination of surgery, chemotherapy and/or radiation, but they all metastasize in the mind. My leukemia stems from a permanent manufacturing error in the marrow. It can be pushed back but never eliminated. As a result, I’ve thought about cancer every day since July 8, 2011. My good cancer makes me acutely aware that life itself is terminal.

Leukemia makes the weight of mortality more pressing because my health can go sideways in a flash. Someone reading this might think, Sure, but so could mine! And they’d be right.

In the film Casablanca, Rick Blaine (Humphrey Bogart) describes the morally compromised Chief of Police as “just like any other man, only more so.” I’ve heard the joke redeployed any number of times to indicate an increased sensitivity to difficulty in a given subset of people. For example:

Q: What’s the difference between an addict and a normal person?

A: An addict is exactly like a normal person, only more so.

We all labour under the existential burden of our own mortality. A good cancer doesn’t change that, but it does intensify the reality. It booby traps the walk toward the grave. In this sense, living with a good cancer is exactly like living without one. Only more so.