The Wave

It takes only a moment for the blank stare of a stranger to erase me.

We are pedalling up the final stretch of Togwotee Pass in western Wyoming, on mountain bikes loaded with camping gear, food, and water, partway through a 3,000 km journey down the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route. The long climbs turn our legs to rubber and chip away at our middle-class stores of resilience. Togwotee Pass is not the toughest climb on the trail, but it’s one of the longest—27 kilometres at grades between 4 and 6%—and takes us more than three hours.

At the summit, I pass a road cyclist coming the other way. His tight riding gear, the shaped tubes of his carbon bike, and his standing effort to crest the final rise tell me he is a serious rider. I wave, but he looks right through me. This should not matter, but it does.

*

Maureen and I have struggled up the 27 km slope in the midst of a fight. It was -8C when we woke in our tent this morning. We ate breakfast at sinks in the campsite's laundry hut and studied the map of the day’s route. She traced her finger up the long elevation profile of the pass and said, “I don’t think I can do this.”

It was a simple expression of anxiety about the challenge ahead, but I chose to overreact. "Maybe we should just pack up and forget the rest of the trip," I said.

"Good idea!”

It was a reminder of the negative efficiency of a 30-year relationship: we sometimes skipped preliminary escalations and went straight to the core of conflict. I cleaned my breakfast bowl with as much clattering impatience as I could manage, then stomped back to load the bikes.

We've been on the road for three weeks—across more than 1,000 kilometres of Montana and Idaho forest roads, rail trails, and single-track. The hot days and grinding climbs weigh as heavily in our minds as in our legs. Maureen sometimes blames me for leading her into the trap of this mammoth excursion, so I heard nothing but recrimination in her complaint about the day ahead. “Why are we doing this?” she sometimes asks when she’s forced to push her bike up a steep section of trail. I ignore the gripes, even though I am equally guilty of hating the rough roads and the brutal ascents and the sheer effort required by this adventure.

We ride up Togwotee pass in silence. When one of us stops for water, the other rides past without acknowledgement and takes a break further up the road. After 31 years of marriage, our fight is more ritual than deep conflict. It may end when one of us can no longer keep a straight face, but it could also get worse.

My encounter with the road cyclist comes just after I crest the summit of Togwotee Pass. The pavement tips downward, and in seconds the strain of the climb dissolves from my shoulders and legs and lower back. I sit up in my saddle and smile. A moment later, Roadie approaches the summit from the eastern slope. I open a hand to acknowledge our shared moment on opposite sides of a similar challenge. He turns his head in my direction and holds it steady. His hands remain on the bars of his bike. No nod, no wave—but the message is clear enough: you’re on a mountain bike. And you’re touring. We are not the same.

I should know better, but the dismissal burns. Roadie’s contempt reminds me of the way we project our need for status onto unsuspecting strangers.

*

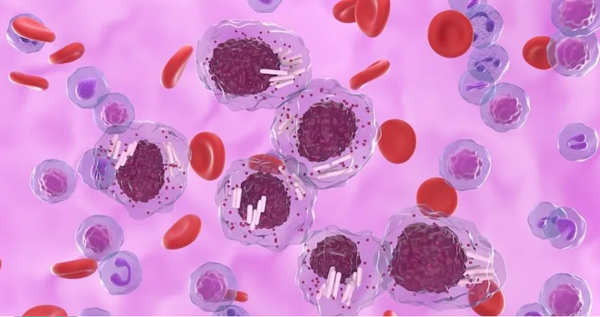

When I was diagnosed with chronic leukemia in 2011, I knew I wanted to travel more. Maureen supported every adventure. Over the next few years, we journeyed by motorcycle through 40 American states and from Victoria to Toronto, zig-zagging through backroad North America to see the sights, enjoy the food, and collect photographs of our adventures. I imagined a time when I might spend a long stretch in a hospital bed, and I wanted pictures to scroll through and memories to relive.

After more than 30,000 kilometres on the motorcycle, my health was holding, but my weight had ballooned. We traded the comfort of a touring motorcycle for the demands of pedal bikes. On our first bicycle tour, we rode 2000 kilometres from Ottawa east through the maritime provinces. The trip that brought us to the western slope of Togwotee Pass would end in Denver, 1500 kilometres south—if Maureen was willing to keep going.

Despite the distances we had travelled on bicycles, we did not see ourselves as serious cyclists. We logged more miles than most people, but in cycling culture, seriousness is often measured by the ability to emulate professional riders. We were bottom-feeders. We covered long distances, but we rode too slowly and in chunks too small to call ourselves hardcore.

At its best, riding a bicycle made me feel like a kid—free and physically legitimate in a small but important way. When Roadie blew me off with his blank stare, he reminded me that I took myself more seriously than I had been willing to admit.

*

A few years ago, not long after our return from a moto tour that took us to the rim of the Grand Canyon, I spent an afternoon talking motorcycles on the front porch of my friend Richard’s house. He had ridden and wrenched bikes since adolescence and now dabbled in restorations with his grown sons. The subject of the rider’s salute came up—the tendency of motorcyclists to raise a hand to acknowledge fellow riders as they passed.

"I don't wave at scooters,” I said. This was part of the code. Gang riders didn't wave at anyone outside the gang; many Harley riders didn’t acknowledge non-Harley riders; people on real motorcycles didn’t wave to scooters.

"I don't know,” he said. "They're out there just like anybody else."

Richard had been an angry young man in his youth, and I was surprised that his long history with motorcycles had delivered him to a position of such magnanimity. He was right, of course. A bike of any description is a relatively dangerous way to travel. Anyone on two wheels takes the same risks and enjoys similar rewards. The wave is an acknowledgement between riders that they are bound by the endeavour.

After my conversation with Richard, I started waving at scooters.

On our bicycle trip down the Rockies, I was struck by how many motorcycle riders waved at us. When ADV riders—“adventure" motorcyclists—waved at touring bicyclists on gravel roads, they were saying, "You're out here just like us.” In the backcountry, everyone waved from their vehicles. It was a simple acknowledgement. "There you are," it said.

*

In August of 2013, on our return from a motorcycle tour through the Deep South, we were waiting in the ferry line-up to return home to Vancouver Island. After we climbed off the bike and removed our helmets and jackets, I noticed two women through the open window of a nearby van. One was bald. The other was breathing through a ventilator. It’s not my nature to introduce myself to strangers, but I had something in common with these women. I was walking toward them almost before I understood why. The bald woman in the passenger seat shifted continually, micro-adjusting her posture to find the least uncomfortable position. From my own chemo sessions, I recalled the hybrid sense of restlessness and exhaustion that followed time in the chair.

"Treatment trip?" I said.

"Yeah." The driver tilted her head back and gulped air.

"Leukemia," I said, tapping my chest. "I was treated last year."

The bald woman looked up at me. For a moment the discomfort left her eyes and she smiled.

I don’t remember what we talked about, exactly, but we shared a belly laugh before I said goodbye. I was moved by the unvarnished intimacy of the exchange. We were complete strangers, but we shared a limited intimacy nonetheless.

I often think of those women—60ish, one of them breathing with the help of a machine, the other with a fine peach fuzz on her scalp—and our instant connection. The details of our respective conditions didn’t matter. We were the same.

*

Two days before the climb up Togwotee Pass, a pack of BMW adventure riders passed us on large-displacement motorcycles much like the one we had travelled on. A few minutes later, we discovered the group roadside, facing the aftermath of a crash.

The crash victim was on his knees, limbs and brain working well enough to crawl. He would need to be checked for internal damage, but at a glance, it looked like he'd be okay.

His bike lay on its side in the bushes beside the wide dirt trail. I set my bicycle down and followed two others to the crash site. "I’ll help you with that," I said.

"We're on a group tour here," said one of the riders, a tall guy in his 50s with white hair and a carefully trimmed fu manchu. He used group to build a fence around the situation. His tone said, "Move along."

I get that this was a moment of great stress for him, but the incident reminded me how quickly things can change and how foolish are the rituals of exclusion. If Fu Manchu were down on the trail and we had been first to reach him, he would have accepted help, group or no group.

*

A few seconds after I am dismissed by Roadie at the top of Togwotee Pass, I pull to the shoulder and wait for Maureen. We’ve been together for 35 years and have survived a full range of personal and family battles. We've managed by including one another. She’s out here for me, riding as much as 120 kilometres a day and fighting up every hill.

We’re not out here to battle dedicated road riders.

When she rounds the last corner and approaches the summit, I smile and wave. There’s a chance this could backfire—that the long morning silence could have galvanized her threat to abandon the journey—but when she stops beside me, it’s like the fight never happened. I hand her my coldest bottle of water and she takes a long drink. Then she meets my eyes for the first time in hours.

“Hey,” I say, grateful for her forgiveness, “there you are.”